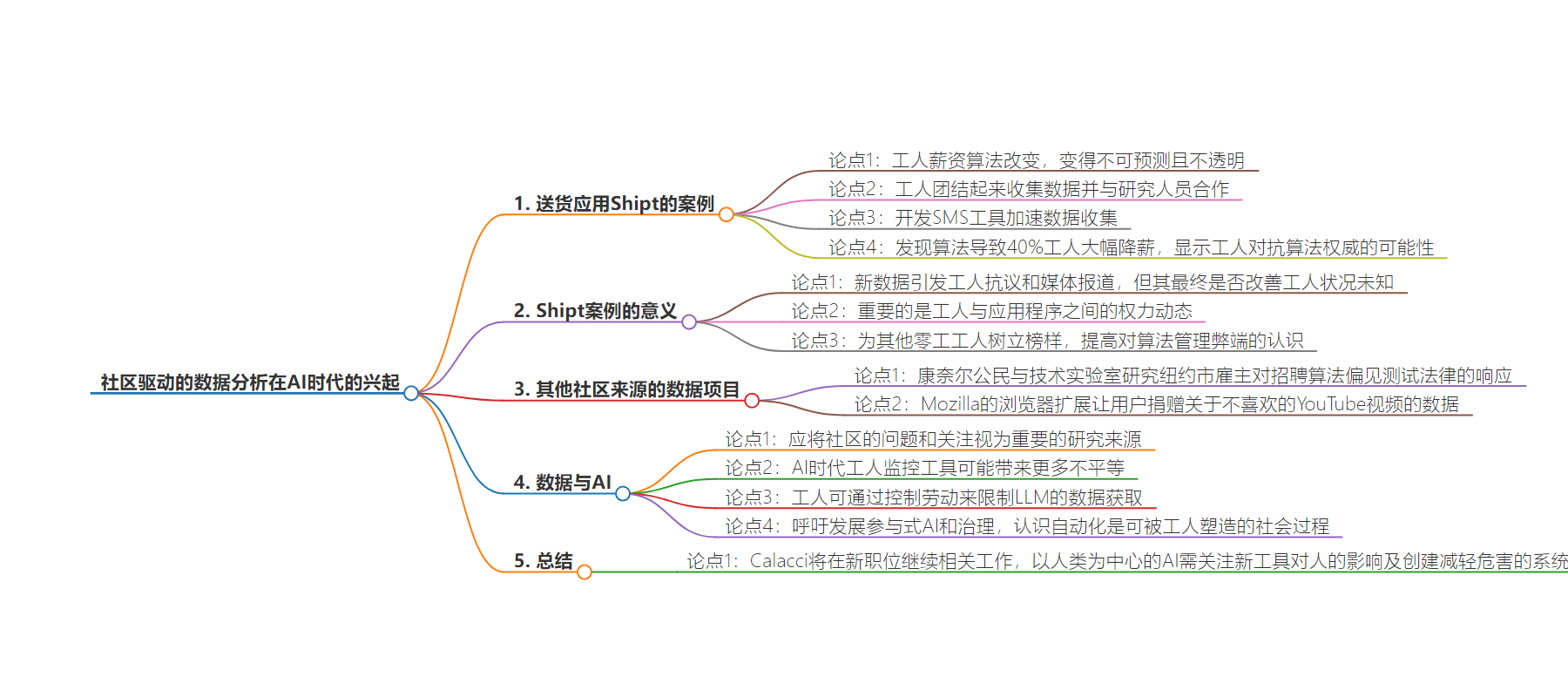

包阅导读总结

1. 关键词:社区驱动、数据分析、算法管理、工人权益、人工智能

2. 总结:本文主要探讨了社区驱动的数据分析在AI时代的兴起,以Shipt工人维权为例,展现了工人通过收集数据对抗算法不透明,还提及其他社区数据项目,强调工人应争取对数据使用的控制以保护自身权益,最后指出应实现以人为本的AI。

3. 主要内容:

– 以Dana Calacci对数据分析和受其影响的人的关注开篇

– 以Shipt工人为例

– 工人工资算法改变且不透明

– 工人联合收集数据并与研究人员合作

– 发现算法导致多数工人减薪,彰显对抗算法权威的可能

– Shipt事件的意义

– 引发工人抗议和媒体关注,重要的是改变工人与应用的权力动态

– 其他社区数据项目

– 康奈尔公民与技术实验室研究纽约雇主对招聘算法的响应

– Mozilla团队研究YouTube推荐机制

– 关于LLMs

– 指出AI时代工人监控工具可能带来更多不平等

– 工人可控制数据来影响AI发展

– 呼吁发展参与式AI和治理,实现以人为本的AI

思维导图:

文章地址:https://thenewstack.io/the-rise-of-community-driven-data-analysis-in-the-age-of-ai/

文章来源:thenewstack.io

作者:David Cassel

发布时间:2024/7/25 13:28

语言:英文

总字数:1673字

预计阅读时间:7分钟

评分:86分

标签:社区驱动的数据分析,零工经济,算法透明度,工人权利,人工智能在工作场所的应用

以下为原文内容

本内容来源于用户推荐转载,旨在分享知识与观点,如有侵权请联系删除 联系邮箱 media@ilingban.com

Dana Calacci cares about data analysis — but even more, about the people who are affected by it.

Or, as Calacci’s webpage puts it, “I study how data stewardship and analysis can impact community governance. Right now, I’m focused on how algorithmic management is changing the reality of work, how data stewardship and participatory design can help create alternate working futures, and on the data rights of platform workers.”

Calacci provided an example in a July article in IEEE Spectrum — a kind of cautionary tale that arrives at an inspiring conclusion.

But along the way, Calacci also gave hints on new ways of thinking about data, showing how some communities are pioneering a new approach to the ways that data is gathered — and then an even newer approach to how that data gets put to use.

When Gig Workers Unite

Calacci wrote that in early 2020, gig workers for the delivery app Shipt “found that their paychecks had become… unpredictable.” Previously, they had been paid $5 per delivery plus 7.5% of the order amount, but Shipt then added additional factors to their pay algorithm — including mileage driven and shopping time required.

“Since Shipt didn’t release detailed information about the algorithm, it was essentially a black box that the workers couldn’t see inside,” they wrote.

But instead of taking it, Calacci wrote, the workers “banded together, gathering data and forming partnerships with researchers and organizations to help them make sense of their pay data.”

“It was very clear that something else needed to happen — something above just complaining on Facebook groups,” says Shipt worker Willie Solits, who organized their early efforts. In a video from MIT Media Lab, Solits recalled that “we needed to organize and do something about it.”

The workers started by taking pictures of their pay receipts and collating the data. And by that summer, Calacci was brought in to build an SMS-based tool that could scale their data collection faster. “By October of 2020,” they wrote, “we had received more than 5,600 screenshots from more than 200 workers.”

Calacci wrote that the project was exciting because “it was worker-led. It’s driven by measuring the experience of workers themselves … With the help of that tool, the organized workers and their supporters essentially audited the algorithm and found that it had given 40 percent of workers substantial pay cuts.”

But more importantly, “The workers showed that it’s possible to fight back against the opaque authority of algorithms, creating transparency despite a corporation’s wishes.”

What the Shipt Episode Means

The new data led to worker protests and media coverage — though Calacci’s article concedes there’s no answer as to whether it ultimately improved their condition. “We don’t know, and that’s disheartening.”

In a discussion on Hacker News, some commenters argued that the data ultimately showed that more than half the Shipt workers didn’t experience a cut in pay. But Calacci responded on social media that “the real issue was that pay was suddenly opaque and unpredictable.”

So regardless of the fairness of the new algorithm, Calacci thinks what’s important is the power dynamic between workers and the app.

Or, as they put it in the article, “In a fairer world … this transparency would be available to workers by default.”

And in the end, “our experiment served as an example for other gig workers who want to use data to organize, and it raised awareness about the downsides of algorithmic management. What’s needed is wholesale changes to platforms’ business models. ”

And in an article published in April by the National Employment Law Project, Willie Solis, a Shipt worker, wrote that “we were able to prove through crowdsourcing information in our Facebook group that our tips weren’t all coming to us like they should.”

Other Community-Sourced Data Projects

Calacci’s article cited a 2021 event that showcased other inspiring worker-led data projects — as a reminder that “there are researchers and technologists who are interested in applying their technical skills to such projects.”

And in an email interview with The New Stack, Calacci shared more examples of community-sourced data projects.

Cornell has a Citizens and Technology Lab (led by J. Nathan Matias, an assistant professor of communications), created specifically to work with communities “to study the effects of technology on society” — and to test ideas “for changing digital spaces to better serve the public interest.”

In January, the lab’s researchers studied how hundreds of employers in New York City responded to a law requiring them to test their hiring algorithms for bias — with the help of 155 undergraduates. The results? “Out of 391 employers, ” the report read, “18 employers published hiring algorithm audit reports, and 13 posted transparency notices informing job-seekers of their rights.”

But “most employers implemented the law in ways that make it practically impossible for job-seekers to learn about their rights,” the researchers concluded, writing that the law “gives employers extreme discretion over compliance and strong incentives to avoid transparency.”

Mozilla has an advocacy/research team, and among its projects is a browser extension that lets people donate their data about the YouTube videos they’ve regretted watching.

In 2022 Jesse McCrosky, a data scientist, teamed up for a study with Becca Ricks, the Mozilla Foundation’s head of open source research and investigations, to analyze the data donated by 22,722 people. Their conclusion? “People don’t feel they have much control over their YouTube recommendations — and our study demonstrates they actually don’t,” they wrote.

“We found that YouTube’s user controls influence what is recommended, but this effect is meager and most unwanted videos still slip through.”

Their report ultimately recommended that YouTube should “provide researchers with access to better tools,” and that policymakers should “pass and/or clarify laws that provide legal protections for public interest research.”

Calacci said there are numerous additional examples in the 2020 book “Data Feminism,” which promised “a new way of thinking about data science and data ethics that is informed by the ideas of intersectional feminism.”

Starving the LLMs

It’s a topic that Calacci takes very seriously. “I would love to see more researchers treat communities’ questions and concerns as serious sources of inquiry,” they said in our email interview. “Many communities have real questions they want answered about their environment, the technology they use and how it’s impacting their well-being and health.

“These can be translated into rigorous research questions by treating communities as co-researchers — like we did with the Shipt work.”

And Calacci believes the issue is about to become even more important. Their article ends with the possibility of even more inequity when worker-monitoring tools are powered by AI. “The battles that gig workers are fighting are the leading front in the larger war for workplace rights, which will affect all of us.”

Calacci elaborated in an article published last December in ACM Interactions magazine, noting we were already living in a world with “algorithmically determined productivity scores, tracking text communications in the workplace, and software that takes regular screenshots of workers’ computer screens for employer review.”

“In the [large language model] era, all of this surveillance — and the data it creates — turns into potential training material for future AI systems.”

But in a section titled “Starving the System as a Labor Strategy,” Calacci noted “a glimmer of hope” in the way LLMs need human content to train on — “for workers seeking to exert some control over the direction of future AI model development. If workers choose to withhold their labor, they can effectively starve these systems of the data they need to improve.”

In our email interview, Calacci described the outlines of a larger struggle. “Tech workers, along with creative workers more broadly, need to start considering how their data is being used to train systems that control workers in other offices and create new, valuable content through [generative AI]. Their data helps determine what AI systems can do. That means that gaining some legal control over how it’s used is crucial.

“Workers should try and follow in the footsteps of the WGA and SAG-AFTRA in negotiating data protection clauses into their bargaining agreements, or unionizing in order to gain the power to make one,” they told The New Stack. “Without federal or state data protection for workers, this is the best step they can take to help control and direct how technology might impact their workplace in the future. ”

Calacci’s article even lays out the potential for automation to be an empowering tool, calling for the development of “participatory AI and governance.” But, they wrote, “achieving these goals requires more than developing new technologies. It asks for a paradigm shift in how we approach technology in the workplace and automation as a whole.

“Rather than treating automation as an inevitable force that workers must adapt to, we need to recognize it as a social process that can and should be shaped by those it affects most — workers themselves.”

And Calacci will continue this work in their new position as an assistant professor at Penn State in human-centered AI. “For me, human-centered AI means first, surfacing the impacts that new AI tools have on people,” Calacci said in their email.

But in addition, “it means creating systems that mitigate those harms, ranging from designing alternative algorithms and interfaces to deploying adversarial tools to resist or break existing AIs.”

YOUTUBE.COM/THENEWSTACK

Tech moves fast, don’t miss an episode. Subscribe to our YouTubechannel to stream all our podcasts, interviews, demos, and more.