包阅导读总结

1. 关键词:AI 、编程教育、教师、学生、风险

2. 总结:在 AI 时代,计算机科学教师在思考如何教育学生编程,各方意识到 AI 虽强大但有风险,应将其融入课程,培养学生批判评估能力,强调教师作用,关注伦理问题,仍需教授编程。

3. 主要内容:

– 计算机科学教师协会认为应将 AI 工具纳入教育,指出其能快速编码但可能出错,呼吁制定政策规范相关问题。

– Code.org 开展“TeachAI”,发布的报告显示多数教师帮助学生理解 AI 社会伦理问题,强调要让学生学会提问和掌控工具。

– 拉斯维加斯的会议上,专家们强调教师重要性,如谷歌、斯坦福等的代表,指出 AI 虽能生成代码但仍需人工处理,会议也探讨了 AI 的局限和伦理培训等问题。

– 会议中教师们意识到 AI 有潜力但不完美,仍需教授无错误编程,有人因会议结束后的返程问题印象深刻。

思维导图:

文章地址:https://thenewstack.io/in-the-age-of-ai-what-should-we-teach-student-programmers/

文章来源:thenewstack.io

作者:David Cassel

发布时间:2024/8/6 18:49

语言:英文

总字数:1459字

预计阅读时间:6分钟

评分:87分

标签:人工智能在教育中,计算机科学课程,伦理人工智能,教师培训,AI 能力

以下为原文内容

本内容来源于用户推荐转载,旨在分享知识与观点,如有侵权请联系删除 联系邮箱 media@ilingban.com

In a world where AI has created powerful tools for coding, what exactly should computer science teachers tell the young programmers of tomorrow?

On the front lines of the future, educators are grappling with what stance to take — with a little help from nonprofits and professional trade associations. The ongoing discussion offers a unique perspective on a very real need being confronted: to understand where we’re at, in order to define where we want to go.

And it shows that teachers are well aware of the shortcomings and dangers of AI systems — and want their students to be too.

Mass-Produced Errors

The Computer Science Teachers Association is a registered public 501c3 nonprofit focused on “creating a supportive environment for K-12 educators.” And in February the CSTA published some thoughts from Dr. Kip Glazer and Dr. Sonal Patel (both members of the organization’s Equity Fellowship).

“We want to acknowledge that chatbots can code much quicker than a person, which is one of the benefits of automation,” they began their remarks. But “being able to code faster doesn’t mean that the outcome will be better. In fact, we have seen erroneous products being mass-produced by AI generators.”

Nevertheless, they write that the CTSA is “leading the charge to incorporate AI tools into CS education” while “debunking a fatalistic view of the future of the CS field.”

“We firmly believe that a stronger educator voice in the age of AI is critical as the pressure to quickly implement AI into the education system intensifies.”

As they see it, adding AI to CS curriculums can “equip students with the ability to understand and critically evaluate AI-generated content, address bias issues, ensure transparency and accountability in AI systems, protect student data and privacy, and ultimately, shift the focus towards human-centered computing and learning.”

And despite the newness of the technology, the two fellows were already prepared to make some specific recommendations — including one for public advocacy. “We as educators must demand that all States create strong policies and regulations to address issues related to AI, including bias, transparency, and accountability.”

Learning to Ask Questions

Looking to the future, the education innovation/CS materials nonprofit Code.org has already staffed and operated something called “TeachAI” (partnering with numerous other groups including Khan Academy and the World Economic Forum). Before the annual CSTA conference, the group released a set of three briefs titled “Guidance on the Future of Computer Science in the Age of AI” — in conjunction with the CTSA.

But even there, the briefs show a clear awareness of how AI can come up short. “We need to help students learn to ask questions well,” said Christina Gardner-McCune, an associate professor at the University of Florida. The guidance cites her observation that “We need to teach them to have ownership of these tools.”

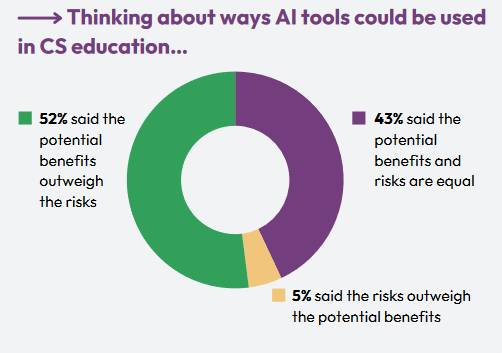

The group’s announcement included results from a spring survey of 364 different primary and secondary CS teachers. And in an encouraging sign, their briefs show that more than two-thirds of the surveyed CS teachers — 66% — said they’ve helped students understand “societal and ethical issues” around AI, with 80% saying their discussions included ethical questions (like bias and privacy) at least once a month. So the teachers are well aware of the risks.

But CSTA board chair Charity Freeman argues that “When it comes to AI education, we do not have the luxury of burying our heads in the sand.”

The group’s first brief focused on why it’s still important to learn programming in the age of AI, noting research showing young coders benefit more when AI augments their skills rather than taking their place.

Even in the IT industry of today, AI-generated code needs human overseers to ensure correctness and to evaluate, debug, and modify AI-generated code (or properly place it in a larger codebase). Human creativity and domain expertise are also still required, the brief argues, though “Learning to program is shifting from focusing on code generation to more code reading, evaluation, debugging, and refactoring.”

And maybe our goals shouldn’t be limited to just training the next generation of coders, the brief argues. “Learning to program offers students a platform for collaborative problem-solving, creative expression, and discovering joy in creating something new.”

In the end, it argues, learning to code has an emotional value. “A small-scale study of primary school students showed that children felt significantly happier, more excited, and more in control after learning to program.”

Heat in Las Vegas

All together the conversation offers some fascinating scenes from our moment in time, as teacher organizations acknowledge the undeniable potential of AI systems — but also their inherent risks, and the strong need for human involvement. And that conversation is already involving lots of education professionals. In July, as temperatures scorched Las Vegas, CS teachers from around the country gathered for an annual conference — including a panel of expects speaking specifically on “CS Education in the Age of AI.”

- Dr. Maggie Johnson, Google‘s director of education and university relations (managing Google’s online learning-at-scale programs).

- Dr. Kip Glazer, who is both an AI enthusiast and the principal of a Silicon Valley high school.

- Dr. Mehran Sahami, a Stanford CS professor and department chair.

- Christy Crawford, a long-time member of New York City’s Department of Education.

Right away, the panel began emphasizing the importance of teachers. “Mehran was first to respond and hit the nail on the head,” wrote Mike Zamansky, a professor at Hunter College creating a new CS honors undergraduate program. “AI can’t transform education, only people (teachers) can transform education… He added that AI can enhance teachers ability to transform education but it’s just a tool.”

And Dr. Maggie Johnson “noted that even if AI can generate code, it still needs to be understood, checked, tested, extended, and embedded.”

University of Washington professor Amy J. Ko shared their own reaction in a post-conference blog post. “My favorite comments were from Christy, who drew a sharp line against corporate product placement in classrooms and curriculum, asked critical questions about the need to understand generative AI’s increasingly obvious limitations for learning, and rejected the idea that school’s purpose is to train employees for tech companies.”

That clear-eyed pragmatism continued in the side sessions following the panel. Even an AI-focused unit from the Amazon Future Engineer program promised to also discuss biases in AI technology…

After the conference CS teacher Alfred Thompson blogged his reaction, pointing out that AI was also a focus of many of the side sessions. In another blog post, Thompson noted several of those sessions were “packed,” adding “So much of what I am hearing at the conference is the need to [view] ethical training as important when talking about AI.”

Thompson shared some key takeaways — some of which were decidedly optimistic. “One is that AI has the potential to allow our students to do more. More complicated projects. More innovative projects.”

But in addition, “there was a reminder that these AIs, including the ones that generate code, are not perfect. In fact, one study at Stanford showed that students using AI generated code with more security holes than students who didn’t use AI. Worse still, the students who did use AI were more confident that their code was good.”

“We’re going to need people who can read, test, and debug code for some time to come. It’s much too soon to stop teaching coding.”

But in the end, the teachers were also given a stark reminder about the importance of bug-free programming. Thompson wrote on his blog that the conference would be remembered as the first big AI conference — if not for what happened afterward. “For many of us, we will remember it as the conference we had trouble getting home from. CrowdStrike is now a ‘dirty word’ for us.

“I am writing this from a hotel room in Las Vegas two days after the conference ended.

“Hopefully I will get home tomorrow…”

YOUTUBE.COM/THENEWSTACK

Tech moves fast, don’t miss an episode. Subscribe to our YouTubechannel to stream all our podcasts, interviews, demos, and more.