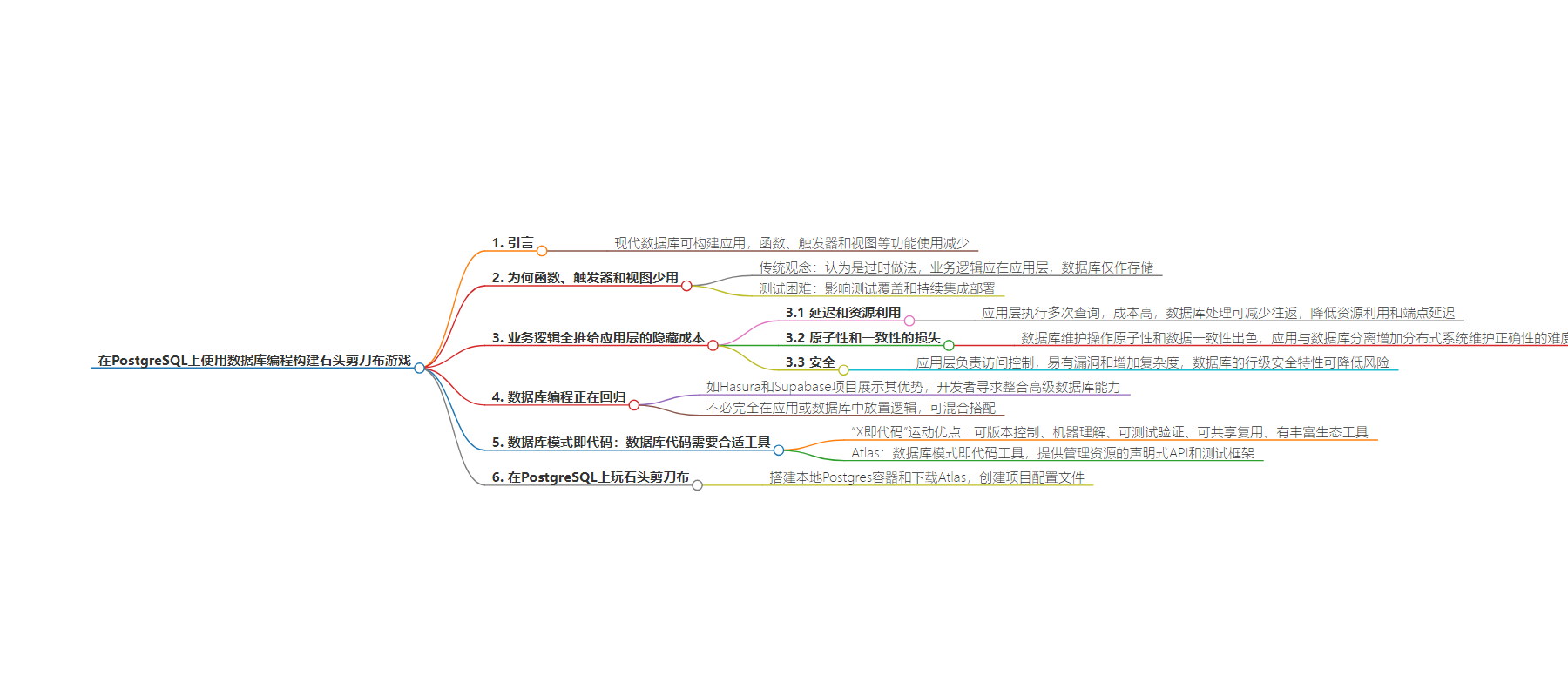

包阅导读总结

1. 关键词:PostgreSQL、数据库编程、应用构建、成本、回归

2. 总结:本文探讨数据库编程,指出其虽因一些原因失宠,但在新发展下有回归趋势。以构建“石头剪刀布”游戏为例,阐述其优势,如减少延迟、保证一致性等,还介绍了相关工具及项目。

3. 主要内容:

– 数据库编程的现状

– 虽数据库可编程且功能强大,但部分功能近年失宠。

– 原因包括认为其过时、测试和部署困难等。

– 仅用应用层处理业务逻辑的隐藏成本

– 增加延迟和资源消耗。

– 损失原子性和一致性,如维护审计日志复杂。

– 存在安全风险和访问控制难题。

– 数据库编程的回归

– 如 Hasura 和 Supabase 展示其优势。

– 提供强大功能,简化应用开发。

– 数据库模式即代码

– 缺乏相关工具曾是问题。

– Atlas 等工具可助力。

– 构建在 PostgreSQL 上的石头剪刀布游戏示例

– 介绍设置步骤。

– 展示如何应用现代软件工程原则。

思维导图:

文章地址:https://thenewstack.io/build-a-rock-paper-scissors-game-on-postgresql-with-database-programming/

文章来源:thenewstack.io

作者:Rotem Tamir

发布时间:2024/8/6 21:09

语言:英文

总字数:4704字

预计阅读时间:19分钟

评分:88分

标签:数据库编程,PostgreSQL,应用开发,Hasura,Supabase

以下为原文内容

本内容来源于用户推荐转载,旨在分享知识与观点,如有侵权请联系删除 联系邮箱 media@ilingban.com

Modern databases are durable, efficient, and programmable data repositories, making them super-potent environments for building applications. However, many database features, such as functions, triggers, and materialized views, have fallen out of fashion in recent years.

This article reexamines this paradigm, given new developments, and shows how to build a database-centric application without sacrificing modern software engineering principles by creating a fully working “Rock, Paper, Scissors” game that runs on a PostgreSQL instance.

Why Are Functions, Triggers, and Views Hardly Used?

Modern databases are more than just a storage layer with an attached query engine. Using triggers, functions, stored procedures, constraints, and views, it is possible to build entire applications without ever leaving your database. So why do modern software engineering teams typically only use a small fraction of them?

As a young developer, everyone around me told me that using these features is an antiquated practice that belonged in the ancient days when DBAs roamed free and monoliths ruled the globe. Modern software, so I was taught, should have a clear separation of concerns — business logic belongs in the app, and the storage layer should be treated as a “repository” — responsible for providing durable storage and satisfying queries.

Furthermore, testing database logic was a pain that would deteriorate our efforts to get good test coverage and benefit from our CI pipelines. Deploying these changes would also be ugly, degrading our efforts to automate delivery with CD.

In short, database programming was seen by many as almost antithetical to the innovation brewing in our industry with the modern Agile and DevOps movements.

The Hidden Cost of Pushing Everything Up to the Application

Pushing all business logic to the application layer and treating databases as mere “repositories” of data has its advantages, that’s for sure. However, let’s consider some of the (not so) hidden costs of this design principle:

Latency and Resource Utilization

Backend server endpoints typically perform multiple queries to satisfy user requests. Each such request involves serializing a request, making a network call, waiting for the database to process it, reading the results from the network card, parsing the result, and often mapping each record into an object in memory.

Pushing application logic back into the database can eliminate costly round-trips, reducing overall resource utilization and endpoint latency.

Loss of Atomicity and Consistency

Modern databases such as PostgreSQL are incredibly adept at maintaining the atomicity of operations and consistency of the resulting data using their ACID properties.

Once your application is split between two components (such as a server and a database) that communicate over the network, you are bound to deal with the challenges of maintaining correctness in a distributed system, effectively forfeiting much of the power that modern relational databases give you for free.

A classic example is maintaining consistent, correct, and durable audit logs for database changes. This task, which is trivial to achieve using trigger functions, becomes a much bigger undertaking when implemented in the application layer.

To maintain correctness, eliminate writes to the database from anything that isn’t the application (including older versions of it that might not have the auditing logic). Secondly, to ensure consistency, ensure that writing to the audit table is always done in the same transaction as writing to the main entity table.

Of course, the main cost here is the complexity of the resulting system and codebase, which can be greatly reduced by using triggers, the native database solution.

Security

Modern applications often need to enforce complex access control rules to ensure sensitive data is accessible only to authorized users. Traditionally, this responsibility falls on the application layer, where user permissions are checked before performing any data operation. However, this approach can lead to security vulnerabilities and added complexity in the codebase, as access control logic must be diligently implemented and maintained across all application parts.

PostgreSQL and Microsoft SQL Server offer similar Row-Level Security (RLS) features, providing a robust solution to this challenge by allowing you to enforce access control policies directly within the database. RLS enables you to define security policies that filter which rows a user can access based on their role or other attributes, ensuring that unauthorized users cannot read or modify data they shouldn’t have access to.

By transferring access control policy enforcement to the database, we can eliminate application development complexity and maintenance costs, reduce security risks, and achieve a better compliance posture.

Database Programming Is Making a Comeback

In recent years, I have observed many engineers and architects in our industry become more aware of the costs of avoiding database programming altogether. Many are looking for better ways to integrate advanced database capabilities into their applications.

This trend is best exemplified by the success of two widely popular open-source projects: Hasura and Supabase.

Hasura is a real-time GraphQL engine that instantly gives you a GraphQL API on a new or existing Postgres database. Leveraging triggers, functions, and RLS (Row-Level Security), Hasura enables developers to build performant, scalable, and secure applications without writing boilerplate backend code. It integrates seamlessly with your database schema, allowing you to define complex business logic directly in the database and simplifying maintenance.

Supabase offers an open-source Firebase alternative using PostgreSQL and leverages PostgREST to provide instant APIs, authentication, and real-time capabilities. By pushing logic to the database, Supabase makes it easy for developers to create robust applications with minimal effort. PostgreSQL’s capabilities for complex queries, data transformations, and access control ensure performance and security.

Both Hasura and Supabase demonstrate the power and efficiency of embracing database programming. Providing organizations with an “instant” backend API on top of a database enables an architecture that pushes application business logic back down into the database, eliminating the need for custom database boilerplate code.

Of course, you don’t have to choose to place application logic exclusively in the app or the database. A completely “backend-less” application may work in some situations. Still, in practice, it is perfectly fine to mix and match by building some logic into pure application/backend code and delegating responsibilities to the database to handle other parts. For this reason, Supabase offers Edge Functions as part of its platform, just as Hasura offers Actions and Remote Schemas.

Database Schema as Code: Database Code Needs Proper Tooling

Looking back at the arguments against pushing business logic down to the database, many of them boil down to the lack of adequate tooling and established strategies for integrating them with modern software engineering practices like automated testing, CI/CD, etc.

The argument goes that working with databases isn’t as robust as working with code. But what if it was?

In recent years, our industry has seemed to think that “X as Code” is a great idea. In a nutshell, the “X as Code” movement is about describing the desired state of a system (whether it’s infrastructure, configuration, or schema) in a declarative way and then having that state enforced by a tool.

So why is having things described as code so great? Here are a few reasons:

- The code can be versioned. This means you can track system changes over time, easily compare states, and roll back as needed.

- Machines understand code. As formal languages, machines can process, analyze, and execute code.

- Code can be tested and validated. By using software testing paradigms, you can ensure that your system behaves as expected in an automated way.

- Code can be shared and reused, allowing us to transfer successful ideas and implementations between projects and teams.

- Code has a vast ecosystem of productivity tools. By using code, you can leverage the tools and practices developed by software engineers over the years.

Atlas is a database schema-as-code tool (full disclosure: I am one of its authors) designed to enable engineers to apply modern software engineering principles to database design. Sometimes called the “Terraform for Databases,” Atlas provides a declarative API for managing database resources as well as a testing framework for writing and running tests.

In the next section, I will show how Atlas can bridge the gap that might prevent some teams from fully utilizing database programming for their workloads.

Playing Rock, Paper, Scissors on Your PostgreSQL

Setting up

To demonstrate how Database Schema-as-Code can be used to apply modern software engineering principles to database programming, let’s build a fun example application – a Rock, Paper, Scissors game (RPS going forward) that will play directly on a PostgreSQL database.

Let’s start by running a local Postgres docker container that will act as our target database:

|

docker run —rm –e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=pass —name rps –p 5432:5432 –d postgres:16 |

Next, download the most recent version of Atlas:

|

curl –sSf https://atlasgo.sh | sh |

Create a file named atlas. hcl to store our project configuration:

|

env “local” { url = “postgres://postgres:pass@localhost:5432/postgres?search_path=public&sslmode=disable” src = “file://schema.sql” dev = “docker://postgres/16/dev?search_path=public” } |

This file defines a “local” environment that will be used to develop our application and manage our local DB (defined in the url attribute). Additionally, we define the project’s Dev Database, a local, empty Postgres instance Atlas that is used for various calculations.

Our Business Logic

Let’s start building our application!

Create a file named schema.sql; this file will contain all of our database resources and logic:

|

— Create enum type “move” CREATE TYPE “move” AS ENUM (‘rock’, ‘paper’, ‘scissors’);

— Create enum type “result” CREATE TYPE “result” AS ENUM (‘win’, ‘lose’, ‘draw’); |

Start by defining the core pieces of the business domain, a move enum corresponding to the different moves a player can make (rock, paper, or scissors), and a result enum with the various possible outcomes of any specific game turn.

Let’s apply our schema to our local database by running:

|

atlas schema apply —env local |

Atlas will connect to our local database and compare the desired state (defined in schema. hcl) with the current state (an empty Postgres) and emit a plan:

|

— Planned Changes: — Create enum type “move” CREATE TYPE “move” AS ENUM (‘rock’, ‘paper’, ‘scissors’); — Create enum type “result” CREATE TYPE “result” AS ENUM (‘win’, ‘lose’, ‘draw’);

? Are you sure?: ▸ Apply Lint and edit Abort |

Let’s approve the plan to apply it to the database.

To confirm everything is in order, re-run the atlas schema apply –env local:

|

Schema is synced, no changes to be made |

Atlas reports that the schema is synced, and we are set to continue our development.

Next, let’s define the core piece of logic in our game, deciding who wins any specific turn. Use a Postgres function to encapsulate this logic. Add the following lines to schema.sql:

|

— Create “turn_result” function CREATE FUNCTION “turn_result” (“player” “move”, “opponent” “move”) RETURNS “result” LANGUAGE plpgsql AS $$ BEGIN RETURN CASE WHEN player = ‘rock’ AND opponent = ‘scissors’ THEN ‘win’ WHEN player = ‘rock’ AND opponent = ‘paper’ THEN ‘lose’ WHEN player = ‘paper’ AND opponent = ‘rock’ THEN ‘win’ WHEN player = ‘paper’ AND opponent = ‘scissors’ THEN ‘lose’ WHEN player = ‘scissors’ AND opponent = ‘paper’ THEN ‘win’ WHEN player = ‘scissors’ AND opponent = ‘rock’ THEN ‘lose’ ELSE ‘draw’ END; END; $$; |

Testing Our Code

Before applying this function to our target database, verify it works correctly. Atlas has a built-in database code-testing framework that can write unit tests for the turn_result function. Create a new file named rps. test.hcl:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

test “schema” “turn_result” { parallel = true for_each = [ {player: “rock”, opponent: “rock”, expected: “draw”}, {player: “rock”, opponent: “paper”, expected: “lose”}, {player: “rock”, opponent: “scissors”, expected: “win”}, {player: “paper”, opponent: “rock”, expected: “win”}, {player: “paper”, opponent: “paper”, expected: “draw”}, {player: “paper”, opponent: “scissors”, expected: “lose”}, {player: “scissors”, opponent: “rock”, expected: “lose”}, {player: “scissors”, opponent: “paper”, expected: “win”}, {player: “scissors”, opponent: “scissors”, expected: “draw”}, ] log { message = “Testing ${each.value.player}, ${each.value.opponent} -> ${each.value.expected}” } exec { sql = “SELECT turn_result(‘${each.value.player}’, ‘${each.value.opponent}’)” output = each.value.expected } } |

Define a schema test case named turn_result to verify our logic. Notice a few interesting things about this test:

- Use the for_each attribute to create a table-test style test case that defines the different use cases we want to check.

- Log a message for each test case containing the inputs (player/opponent) and the expected result.

- Then, execute a dynamically populated SQL statement with values from our for_each cases and verify that the output is as expected.

Run the following for testing:

|

atlas schema test —env local |

Atlas prints out:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

— PASS: turn_result/9 (378µs) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing scissors, scissors –> draw — PASS: turn_result/5 (4ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing paper, paper –> draw — PASS: turn_result/7 (4ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing scissors, rock –> lose — PASS: turn_result/8 (4ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing scissors, paper –> win — PASS: turn_result/1 (5ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing rock, rock –> draw — PASS: turn_result/3 (5ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing rock, scissors –> win — PASS: turn_result/2 (5ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing rock, paper –> lose — PASS: turn_result/4 (5ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing paper, rock –> win — PASS: turn_result/6 (5ms) rps.test.hcl:14: Testing paper, scissors –> lose PASS |

Storing Results in a Table

Next, let’s create a new table to store our game history so we can do fun things with it later. Append the table definition to schema.sql:

|

— Create “games” table CREATE TABLE “games” ( “id” integer NOT NULL GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY, “player” “move” NOT NULL, “opponent” “move” NOT NULL, “result” “result” NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (“id”) ); |

Let’s apply our new table to the database:

|

atlas schema apply —env local |

Atlas plans the schema change for us:

|

— Planned Changes: — Create “games” table CREATE TABLE “games” ( “id” integer NOT NULL GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY, “player” “move” NOT NULL, “opponent” “move” NOT NULL, “result” “result” NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (“id”) ); ? Are you sure?: ▸ Apply Lint and edit Abort |

Choose “Apply” to execute these changes on our local database.

Wrapping up the Logic

With the games table ready, let’s create a helper function that will render the result of a specific game to the user:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

— Create “render_result_text” function CREATE FUNCTION “render_result_text” (“opponent” “move”, “result” “result”) RETURNS text LANGUAGE plpgsql AS $$ DECLARE result_text text; BEGIN — Initialize result text with opponent‘s move result_text := format(‘Opponent played: %s. ‘, opponent); — Determine the result and append to result text IF result = ‘win‘ THEN result_text := result_text || ‘Result: You WIN‘; ELSIF result = ‘lose‘ THEN result_text := result_text || ‘Result: You LOSE‘; ELSE result_text := result_text || ‘Result: DRAW‘; END IF; RETURN result_text; END; $$; |

This function will provide the player with feedback on the result of their move, the computer’s move, and the result.

To make sure this function works correctly, let’s add a test case for it:

|

test “schema” “render_result_text” { parallel = true for_each = [ {player: “rock”, opponent: “scissors”, result: “win”, expected: “Opponent played: scissors. Result: You WIN”}, {player: “rock”, opponent: “paper”, result: “lose”, expected: “Opponent played: paper. Result: You LOSE”}, {player: “rock”, opponent: “rock”, result: “draw”, expected: “Opponent played: rock. Result: DRAW”}, ] log { message = “Rendering ${each.value.player}, ${each.value.opponent}, ${each.value.result}.” } exec { sql = “SELECT render_result_text(‘${each.value.opponent}’, ‘${each.value.result}’)” output = each.value.expected } } |

In this test, we take some likely input combinations and ensure the output is correctly printed out. To verify everything works as planned, we can run the following tests:

|

atlas schema test —env local —run render_result_text |

Notice the –run render_result_text flag to run a specific set of tests instead of the entire suite. Atlas runs the tests and prints out the result:

|

— PASS: render_result_text/3 (613µs) rps.test.hcl:30: Rendering rock, rock, draw. — PASS: render_result_text/1 (6ms) rps.test.hcl:30: Rendering rock, scissors, win. — PASS: render_result_text/2 (6ms) rps.test.hcl:30: Rendering rock, paper, lose. |

Great, our code is stellar! Let’s move on to implementing the final pieces for our game. Append the following resources to your schema. hcl file:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

— Create “random_move” function CREATE FUNCTION “random_move” () RETURNS “move” LANGUAGE sql AS $$ SELECT move FROM unnest(enum_range(NULL::move)) move ORDER BY random() LIMIT 1; $$; — Create “play” function CREATE FUNCTION “play” (“player” “move”) RETURNS text LANGUAGE plpgsql AS $$ DECLARE opponent_move public.move; game_result public.result; result_text text; BEGIN — Ensure opponent_move is assigned properly SELECT random_move() INTO opponent_move; — Calculate the result using the turn_result function SELECT turn_result(player, opponent_move) INTO game_result; — Insert the result into the games table INSERT INTO games (player, opponent, result) VALUES (player, opponent_move, game_result); — Render the result text using the render_result_text function SELECT render_result_text(opponent_move, game_result) INTO result_text; RETURN result_text; END; $$; |

Declare a new helper function named random_move which picks a random move on behalf of our computer opponent and the primary function for our game: play. Briefly, this is what happens when our user invokes play:

- The opponent chooses a random move.

- Calculate the result of the turn using turn_result

- Insert the result into the games

- Use the render_result_text function to return some excellent feedback to our users.

Let’s write another test case that verifies that our logic works:

|

test “schema” “play” { exec { sql = “select play(‘rock’)” } assert { sql = “select exists(select 1 from games where player = ‘rock’ and opponent in (‘rock’, ‘paper’, ‘scissors’) and result in (‘win’, ‘lose’, ‘draw’))” } } |

Running the test using atlas schema test –env local –run play:

Great, our logic works! Let’s apply this to our local database and try it out. Running atlas schema apply –env local:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

— Planned Changes: — Create “random_move” function CREATE FUNCTION “random_move” () RETURNS “move” LANGUAGE sql AS $$ SELECT move FROM unnest(enum_range(NULL::move)) move ORDER BY random() LIMIT 1; $$; — Create “play” function CREATE FUNCTION “play” (“player” “move”) RETURNS text LANGUAGE plpgsql AS $$ DECLARE opponent_move public.move; game_result public.result; result_text text; BEGIN — Ensure opponent_move is assigned properly SELECT random_move() INTO opponent_move;

— Calculate the result using the turn_result function SELECT turn_result(player, opponent_move) INTO game_result;

— Insert the result into the games table INSERT INTO games (player, opponent, result) VALUES (player, opponent_move, game_result);

— Render the result text using the render_result_text function SELECT render_result_text(opponent_move, game_result) INTO result_text;

RETURN result_text; END; $$; ? Are you sure?: ▸ Apply Lint and edit Abort |

Trying out the Game

After approving the plan, let’s now create an interactive session on the database to try our game out, run:

|

docker exec –it rps psql –U postgres |

An interactive psql session appears:

|

psql (16.2 (Debian 16.2–1.pgdg120+2)) Type “help” for help.

postgres=# |

Trying our play function:

|

postgres=# select play(‘rock’); play ————————————- Opponent played: rock. Result: DRAW (1 row) |

That was close. Let’s try again:

|

postgres=# select play(‘rock’); play ——————————————– Opponent played: scissors. Result: You WIN (1 row) |

Hooray, we won! Now, you have a fully working Rock-Paper-Scissors game on your Postgres database.

Modern CI/CD for Databases with Schema as Code

A tool that can run automated tests and declaratively apply (i.e., deploy) schemas to your database from code is a solid foundation for building CI/CD pipelines to automate our application’s software delivery process.

For the sake of brevity, we will not demonstrate today exactly how Git (or other source control systems) and CI/CD pipelines integrate into the mix.

Firstly, to enjoy the benefits of managing our database schema as code, we should place our schema definition and test files under source control. By being under source control, our schemas are now versioned and have a clear audit trail of how they evolved.

Secondly, during the CI phase, we should employ various automated checks to ensure that any proposed changes work and do not break any existing behavior. One such obvious check is to run the schema test command on every commit.

Furthermore, testing that any planned schema changes will be applied successfully is essential. This can be done by spinning up a database with a copy of the existing schema (either directly from the database or from the schema in the most recent commit to our main branch) and applying our recent schema there, ensuring everything works smoothly.

Finally, during the deployment phase, we can use the schema apply command to automatically deploy our most recent schema, just as we did during local development.

Atlas comes pre-packed with a comprehensive set of GitHub Actions to help you automate this process. Of course, modern database CI/CD is a broad topic — if you would like to learn more about Atlas’s approach to this problem, refer to the relevant guide.

Conclusion

This short example demonstrates how Database Schema as Code tools like Atlas can apply tried-and-tested software engineering practices, such as managing resources as code and testing, to database programming.

In conclusion, leveraging modern databases and tools like Atlas allows us to integrate robust database programming into our development workflows to enhance performance and security while simplifying our codebases. Even though this was a contrived example, I hope our little game illustrates some benefits of embracing database programming.

Over the years, database programming has become somewhat of a lost art, so I believe it’s worth investing in our database manuals to learn more about their hidden powers.

In this article, we have shown a glimpse of Atlas’s capabilities, which is by no means a comprehensive guide. If you want to learn more about Database Schema as Code and Atlas, a more complete “Getting Started with Atlas” guide is available on the Atlas documentation website.

YOUTUBE.COM/THENEWSTACK

Tech moves fast, don’t miss an episode. Subscribe to our YouTubechannel to stream all our podcasts, interviews, demos, and more.