包阅导读总结

1. 关键词:心理安全、科技行业、创新、员工留存、风险承担

2. 总结:本文探讨了心理安全在科技行业的重要性,包括其定义、作用及在艰难时期的意义,指出心理安全有助于创新、员工留存和有效协作,即便在形势严峻时也不应被忽视。

3. 主要内容:

– 心理安全的定义

– 由Amy Edmonson提出,是团队成员对团队人际风险承担的共同信念

– 包括能毫无顾虑地表达想法、提出问题等,且非个人所有和静态的

– 心理安全的重要性

– 是创新和迭代的核心,影响生产力和利润

– 影响个体,如SCARF模型中的各要素

– 利于员工留存,降低离职率

– 与创新和协作的关系

– 促进创新,降低风险

– 与有效协作直接相关

– 艰难时期心理安全的意义

– 并非与艰难决策对立,领导者应遵循其价值

– 即便有AI趋势,心理安全仍重要

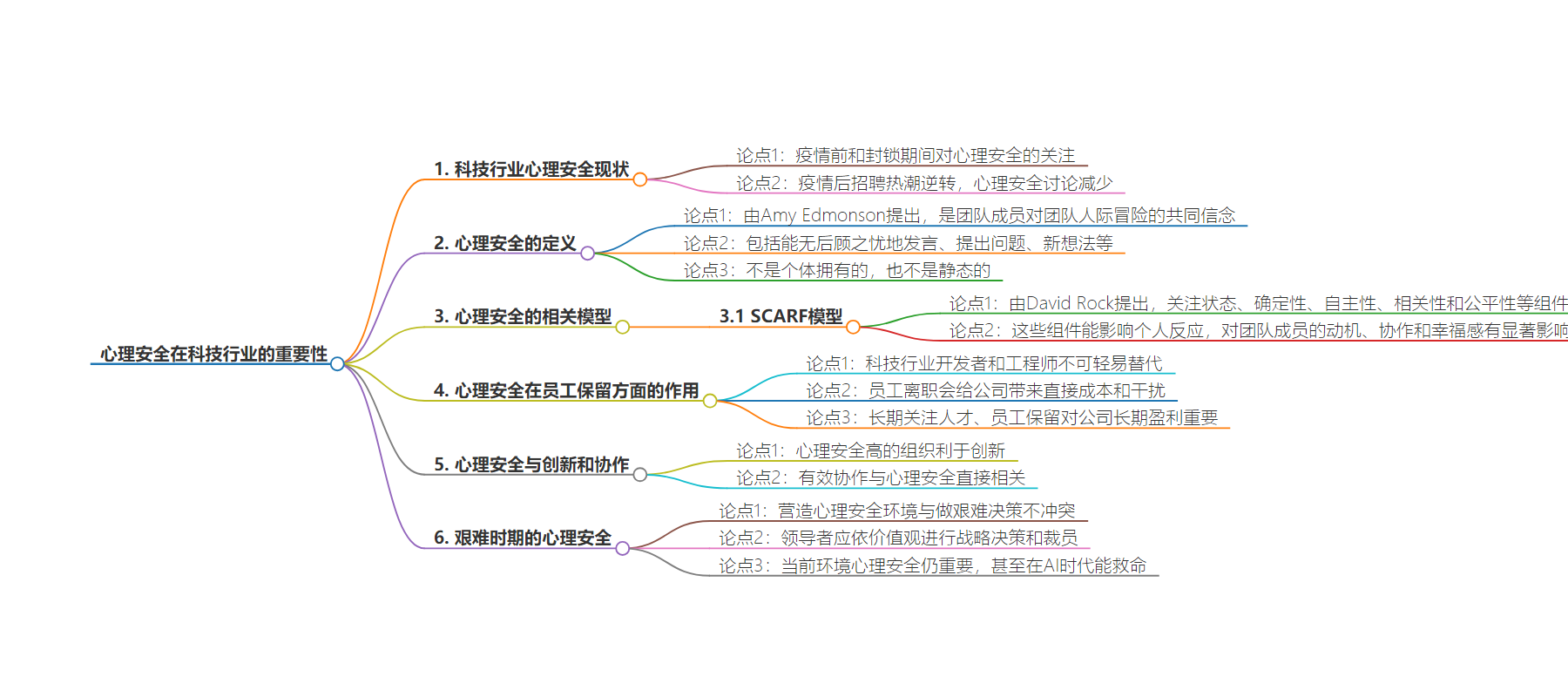

思维导图:

文章地址:https://thenewstack.io/whats-psychological-safety-and-why-does-tech-need-it-now/

文章来源:thenewstack.io

作者:Joe Fay

发布时间:2024/8/2 18:40

语言:英文

总字数:1506字

预计阅读时间:7分钟

评分:85分

标签:心理安全性,科技行业,员工留存,创新,领导力

以下为原文内容

本内容来源于用户推荐转载,旨在分享知识与观点,如有侵权请联系删除 联系邮箱 media@ilingban.com

Before the pandemic, every tech conference worth its salt had at least one session about psychological safety, and during lockdown, companies were upfront that we should all “be kind.”

But the abrupt reversal of the post-pandemic hiring boom has seen brutal headcount reductions across the tech industry —and a lot less talk about psychological safety.

So, was the tech industry only ever paying lip service to concepts like psychological safety? Is it too “touchy-feely” for these times of tighter budgets and more discerning investment?

Perhaps we could all do with a refresher on what psychological safety is — and what it isn’t. Because the thing is, when implemented correctly, it’s central to the innovation and iteration that fuels productivity and profit.

Making It Safe To Take Risks

The term “psychological safety” was first coined by Amy Edmonson, Novartis professor of leadership and management at the Harvard Business School. Edmonson defines psychological safety as a “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.”

That risk-taking includes being able to speak up — whether that’s delivering bad news, owning up to a mistakeor being critical about a project — without repercussions, Andrea Dobson, a psychologist based in London, told The New Stack.

But it can also mean raising potential problems, new ideas, alternative approaches or simply asking for help, said Dobson, head of talent at Container Solutions, a cloud native engineering consultancy.

Psychological safety is not something “that an individual has,” she said. And it’s not static: “Somebody might enter the room, and that belief might shift because of how people might have experienced … that individual.”

Edmondson placed psychological safety as part of a wider concept of the “learning organization,” Dobson added. Such places support collaboration, experimentation and continuous improvement.

Which are, of course, also phrases we can expect to hear in cloud native and DevOps organizations and conferences.

Tom Geraghty, a former CTO who has founded Iterum, a company focused on training organizations in psychological safety, told The New Stack that the concepts of psych safety have even deeper roots — for example, in airline settings or in medicine, where it became apparent that not raising concerns has critical implications.

When it comes to aviation, for example, “If people don’t speak up with a concern saying, ‘We need to stop,’ or ‘We need to change our cause of action,’ then someone can die,” Geraghty said.

It might seem that technology, as a comparatively young industry, hasn’t had as long to evolve these understandings. Developers might not feel as connected to outcomes as medical staff or pilots. Historically, Geraghty suggested, there might not have been that “visceral force” to speak up about an issue, when individuals might think, “Worst case, it might result in a bit of downtime.”

The SCARF Model: The Components of Safety

But that’s a rather complacent position, given the role of tech in medical settings, critical infrastructure and so on. We should all be extremely concerned if the developers of the operating system running our semi-autonomous vehicle didn’t feel free to speak up about a potential problem.

And psychological safety, or the absence of it, can certainly have a visceral impact at the individual level.

The hard part about software development isn’t “figuring out the problem, or coming up with the solution, or writing the code,” Teddy Bartha, a UX designer at Grafana Labs, told The New Stack.

Instead, she said, “the organizational coordination, and making sure that everyone feels empowered and motivated and has ownership, is the really hard part.” And psychological safety is key to this.

Bartha cites the SCARF model developed by David Rock, founder and CEO of the NeuroLeadership Institute, as helping make sense of these issues. SCARF focuses on components — such as status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness — and how these can influence how individuals respond. These can in turn have a dramatic effect on team members’ motivation, collaboration and well-being.

“For me, it’s provided a helpful framework and label to think about when things are going well, and also when they’re not going well.”

Psychological Safety’s Role in Employee Retention

And even if a lack of psychological safety might not always mean human lives are at stake, the organization overall could be imperiled.

In the traditional factory model, workers might — rightly or wrongly — be thought of as easily replaceable. That’s not the case with the developers and engineers who write code and keep digital infrastructure up and moving forward.

“We rely on the people who work for us to bring their knowledge and their skills, their competencies into developing and making our businesses successful,” Dobson said. “If they leave, they take their knowledge and their experience with them.”

That means an immediate cost to the company in the shape of recruiting costs, as well as the disruption that comes with onboarding new hires.

But this isn’t just a short-term issue. Bartha described Grafana as a “long-term greedy” company, which means instead of focusing on short-term returns, it is “thinking what’s going to make me profitable in the long term.”

And that means focusing on talent, employee retention and helping people make the most of their careers in the company over the long term, Bartha said, “rather than putting pressure on the talent to deliver something tomorrow.”

Data over more than a decade shows that psychological safety drives team success and lowers retention. Google’sProject Aristotle, begun in 2012, found it to be one of the most important factors in determining whether a team was successful or not.

And a study released in January by the Boston Consulting Group found that organizations that foster a psychologically safe working environment are twice as likely to retain white, male, non-LGBT employees as those without psych safety —and even more likely to retain women, people of color, and LGBT workers.

Risk-Taking and Collaboration

More importantly, when team members don’t feel free to take risks, their ability to innovate becomes limited.

“Innovation is best done in an organization that has a high psychological safety,” Dobson said. “Why? Because people are not scared to take a risk. Usually in that space is where innovation happens, where we just try things out, regardless of whether it’s going to work or not.”

Indeed, psychological safety is important as a baseline, she explained. “Because it can impact risk, you can reduce risk by upping your innovation.”

As some companies look to force employees back to the office, they often justify it by claiming they want to encourage collaboration. And effective collaboration is directly linked to psychological safety.

“My advice to those leaders would be make sure you have a culture in place that you actually want people to come in and stay,” Dobson said. “If that’s something you really, really think it’s important for your business.”

Whether you’re a leader or not, psychological safety can be built in small steps. “I’ve heard Amy Edmondson say that one of the best ways of creating psychological safety is to pretend it already exists,” said Geraghty.

“Modelling” some of those behaviors — asking questions, suggesting ideas, admitting mistakes — can go a long way. Sometimes, he said, it’s the newest people on a team “that have a little more power in being able to ask the ‘stupid questions.’”

Psychological Safety, Even in Tough Times

But sometimes the economy chills, and concepts like psychological safety seem to move into the “nice to have, but … ” column. But they shouldn’t.

Cultivating a psychologically safe environment is not inimical to making tough decisions, according to Dobson: “If you just have psychological safety and no accountability, that’s not good for business, either.”

But how leaders conduct strategic reviews, and carry out layoffs, if necessary, should be guided and driven by the values they claim to adhere to as a business — including a commitment to psychological safety.

In the wake of a major reorganization, leadership teams should be asking themselves, “We’ve done this restructure: Is there any way we could have improved on this?”

The bottom line, Geraghty pointed out, is that people who are concerned that speaking up might mean they could be fired will keep silent. But if they do so, and issues are never addressed, more companies are likely to find themselves running into trouble.

The current environment might well seem less friendly to psychological safety. Teams might feel under pressure to deliver products or profits more quickly, whatever the cost.

But arguably, psychological safety and related concepts are more important than ever — even as some tech leaders contemplate AI taking over coding.

Because decision-makers might save their company if an environment is created where staffers, clients and leaders are all comfortable saying, “Hang on a minute, I’m not sure about that.” And in an era during which AI is taking over critical functions, it could even save a life.

YOUTUBE.COM/THENEWSTACK

Tech moves fast, don’t miss an episode. Subscribe to our YouTubechannel to stream all our podcasts, interviews, demos, and more.